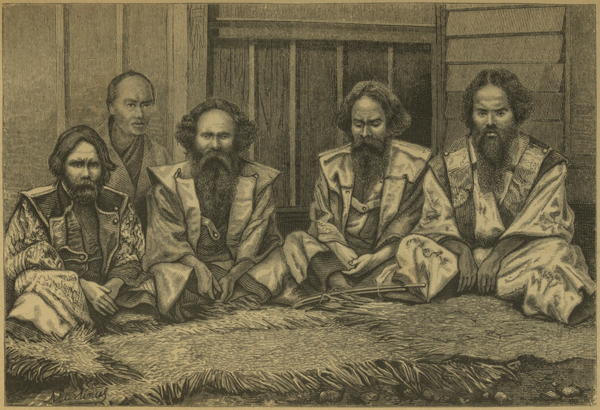

In December 1864, William Martin Wood (1828-1907), a British-Indian journalist, presented a paper to the Ethnological Society of London on The Hairy Men of Yesso.

Yesso was the English rendering for Ezo, or Hokkaido, as it is now known. “The Hairy Men” were Wood’s description of the Ainu people, or Ainos as Wood and others termed them.

“It may seem a thankless task to describe a people whose race is evidently doomed to extinction. It generally happens also, that in the isolated residue of any declining race, its repulsive peculiarities become more strongly marked. Some effort of humane feeling is required in such cases, in order to recognise those traits in virtue of which the perishing fraction may claim its kinship with the great family of mankind. Such an outcast race yet lingers in the island of Yesso, the most northern portion of the empire of Japan. These aborigines are named “Ainos” or “Mosinos” – the “all-hairy people”, this last being a Japanese term which marks their chief physical peculiarity. Their number is estimated at about fifty thousand”.

Newspaper reports of his talk seem to have caught the eye of the Boorn family, proprietors of an equestrian circus which had undergone various incarnations since 1857 and by 1864 was claiming to be a Russian circus. Other “wild men” such as “the Zulu Kaffirs” had appeared at circuses and menageries from 1859 to the early 1860s.

Boorn claimed that the “wild men of Yesso” he started to exhibit at his circus from April 1865 had been captured by her Majesty’s ship Constantine and brought to New York in January 1865. There is no record of such an event occurring.

According to a later newspaper report, Mr Boorn had in fact approached the Strangers’ Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders to ask for applicants who were willing “to come and perform a horde of wild men in his circus, at a salary of 30s. per week.”

Two Africans and two Indians were recruited, and their first appearance was in Chepstow. According to the local newspaper,

“the town was quite enlivened by the visit of Boorn’s clever company of equestrians, accompanied by a “Horde of Wild Men,” supposed to have arrived from the Island of Yesso of the empire of Japan. This proved a very attractive spectacle to the populace, and the procession at one o’clock was a very gay one, reaching the entire length of the principal street. The dresses of the equestrians were very taking, and the procession altogether was highly attractive.

The attendance at the afternoon performance was a paying one, and in the evening a numerous, if not quite so select an audience, warmly applauded the varied performances of the riders, acrobats, tumblers, &c. The entertainment was agreeably varied by the talented and humorous comic vocalist, Mr Joe Holbrook, who convulsed the audience by his ludicrous acting and singing. The entertainment concluded with the exhibition of the “Wild Men” who went through their savage performances to the great terror of many of the audience, while others looked upon them as “got up” for the occasion, be this as it may, there is no question of its being a striking novelty.

Chepstow Weekly Advertiser – Saturday 08 April 1865

The next month, Boorn’s Russian Circus visited Cambridge

“and caused no little excitement, owing to the fact of the proprietor bringing with him, among other attractions, a horde of wild men from Yesso, in Japan; and these men had been placarded in picture bills as of the most savage character. Two men and a woman appeared in a grand procession on Tuesday, confined in small den, clothed in their savage habiliments, and certainly looking very ugly specimens of human nature. The proprietor had placed in his bills that the public were cautioned not to too close to the wild men’s den, and to this caution it may perhaps be owing that no one was scalped or eaten but must let our readers into the secret that these wild men were not wild at all, and this important revelation was made in the following manner.

At the Borough Police Court on Wednesday, one of the horde of wild men travelling with Boorn’s Russian Circus, in reality a very intelligent African, applied for an assault warrant against the proprietor under the following circumstances.

The applicant has been in England for nine years, staying at the Asiatic Home in London, which is a building for the reception of blacks of all countries, and about a month since Mr. Boorn wrote request applicant, together with three others, two Indians, and an African who came from the same place as the applicant, to come and perform a horde of wild men in his circus, at a salary of 30s. per week ; and at St. Ives the proprietor, being indebted to the applicant for several weeks’ wages, he (the applicant) would not get into the den to perform, whereupon the proprietor struck him and in the scuffle that ensued one of the applicant’s fingers was broken, and he now applied for warrant against defendant. The Bench told the applicant they had no power to grant the warrant, as the assault was committed out of their jurisdiction, but told him the company had gone to Royston. The applicant thanked the bench, and said he would to the Home again in London and acquaint the manager with the circumstances. We should say that the supposed wild men gave an illustration of their war dance at the performance, and in justice to Mr. Boom we may state that other portions the entertainment were very creditable, but the wild men were certainly delusion and sham. Cambridge Chronicle and Journal 13 May 1865

A few months later, in October 1865, a concerned party wrote a letter to the London Standard:

“A day or two ago I went to a circus that was exhibiting on its way through our town. One of the attractions advertised was “A horde of wild men,” and at the end of the performance large closed van on wheels was dragged into the middle from the side where it had been allowed to remain inside the tent. The wooden sides were then taken down, and five men clothed in skins appeared behind strong iron bars, not quite a foot apart, with the interstices filled up with network wire. Looking upon it one of the ordinary and legitimate hoaxes of circus I approached them amongst the crowd, prepared to recognise under these uncouth garments and dark skins the lineaments and characteristics of Europeans.

In fact I had made my mind, in common with the rest of the spectators, that they were nothing less than boys dressed up to represent savages. Upon closer inspection, however, I began to think otherwise, and wishing to ascertain the truth, I, with one or two friends, stayed behind. After the spectators had left, I found the proprietor, a most civil and obliging man, and began to question him about these men. He answered me without hesitation, and told me that they had been captured by her Majesty’s ship Constantine, off Yesso, at the north of Japan, that they had been brought to England, and let to him for show.

I then asked if he would allow to inspect them more closely. He complied with our request immediately, and led the way to the van, sent for the keeper, and upon the sides being taken down as before, these men were again visible inside. We then had the opportunity of observing them for about half an hour, and hearing them converse in their language, which sounded like a mixture of Spanish and Sanskrit. They are of short stature, and a copper-coloured hue. Their fingers are pointed like an ape’s, and their legs are straight and thin. They speak no language known to Europeans, but by means of signs are induced to go through their performance of moon-worshipping and war-dancing as the conductor informs the audience. The proprietor assured me that they have never been out of this cage, strewed with clean straw, about six yards in length by three in width, since they have been with him, excepting in one instance, when one of them was taken ill; and a woman belonging to the circus mentioned casually in my hearing that one them must have been in there seven months at least.

That human beings, with souls to be saved, should thus be carried about and exhibited like wild beasts is state of things, I should hope, quite unparalled in this free country.. From all I saw of the proprietor I should say they were treated with great kindness ; but what can compensate for loss of liberty and confinement such as this? Ignorant as I am of their previous history, I am equally unable and undesirous of making any comments. I merely wish to put before the public such of the facts as I know, and, if you think it worth while, you will insert in your columns this letter from one who cannot forget that a man, under any circumstances, is still a man.

Despite this plea, the display of the wild men at Boorn’s circus continued. They reappeared in Britain in April 1866, with the claim that they had been exhibited in all the principal cities of Russia, France and Prussia.

At the end of 1866, it was reported that

“A good deal of amusement has been created by the over zeal displayed by the Aborigines’ Protection Society in memorialising the Home Secretary respecting five wild men connected with a Russian circus.

These savages, according to the statements of the showmen, are wild men from Yesso in Japan, who, unlike other eathens, worship the helements, and speak no known language — certainly none known in Heastern Hasier. Being confined in a den like wild beasts, the Aborigines’ Protection Society felt called on to interfere, and accidentally they got hold of a real native of Japan —at any rate, we will believe so—and this gentleman, calling himself ‘Mr Wooyeno Riotaro’—endeavoured to converse with the prisoners. The prisoners’ only answered him by a succession of short, sharp yelps or barks.

This experiment did not satisfy the Society, but they addressed a memorial to Mr Walpole, who answered his correspondents in a gentlemanly letter, full of quiet satire, in which it is more than insinuated that the public and the Aborigines’ Protection Society have been imposed on with respect to the nationality of the five savages, who, it is to suspected, are of Anglo-Saxon descent, and have transformed themselves for a pecuniary consideration.” Glasgow Sentinel – Saturday 29 December 1866

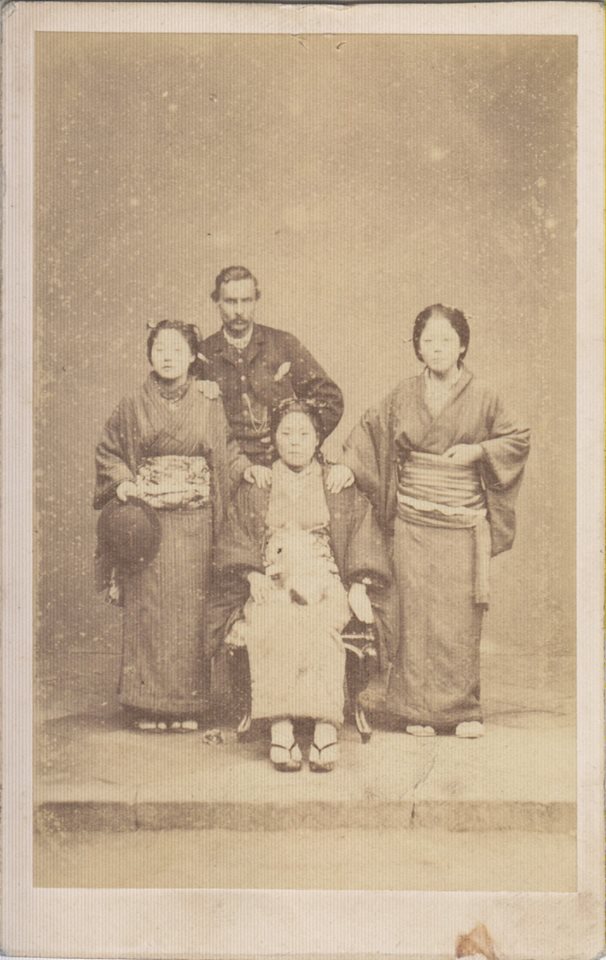

Wooyeno Riotaro (presumably Ueno Ryotaro in modern day rendering) was probably one of the Japanese students who visited Britain clandestinely in 1865, with Thomas Glover‘s support. His name appears in a notice of “arrivals” in town in July 1865 in The Queen: “Jarayah Toranoske, Matsumoora Giungio, Matsumoto Qeigo, Matsumoto Seitchee, Asakura Seigo, Wagaza Canaye, Woskino Seizayemon, Noda Stuhei, Sawai Tetsumah, Tarkahey Masagi, Shigakey Einoske, Wooyeno Riotaro, Hashi Naoske, Sgiwoora Cogio, Micasa Masanaske, Shiota Gongnogia, Shimidzue Cengiro, Seckey Sengio, Jasumi Sengio, and Nagai Joske, from Japan.”

These names do not match well onto the known names of the Choshu students, but an Asakura was one of them (with given name Moriaki, not Seigo), as was Matsumura Junzo (which could be a rendering of Giungio). So it may be they deliberately changed their names in order to avoid identification.

The Russian circus and its wild men of Yesso did not perform in 1867 – they later claimed to have been in America but there is no evidence of this. Benjamin Boorn, the proprietor of the Russian Circus was made bankrupt at the beginning of 1867, and all the costumes, equipment and animals of his Russian circus were put up for auction in Cardiff in February of that year.

Boorn’s Russian Circus reappeared in May 1867 in London, but without the wild men of Yesso. Boorn’s bankruptcy hearings were postponed multiple times throughout 1867 due to various disputes arising from payments for his horses. It is not clear that he was ever discharged and seems to have switched to being a bookseller and stationer in his later years.

It seems Boorn’s son-in-law, James or “Jem” Mace, a pugilist, may have bought up the Boorn’s circus equipment, as he was heading up a “Japanese Circus” with “wild men of Yesso” which was announced in Ireland in May 1868. Mace had been arrested for bare knuckle fighting in 1867 and had obviously decided to find a more legal way to make a living.

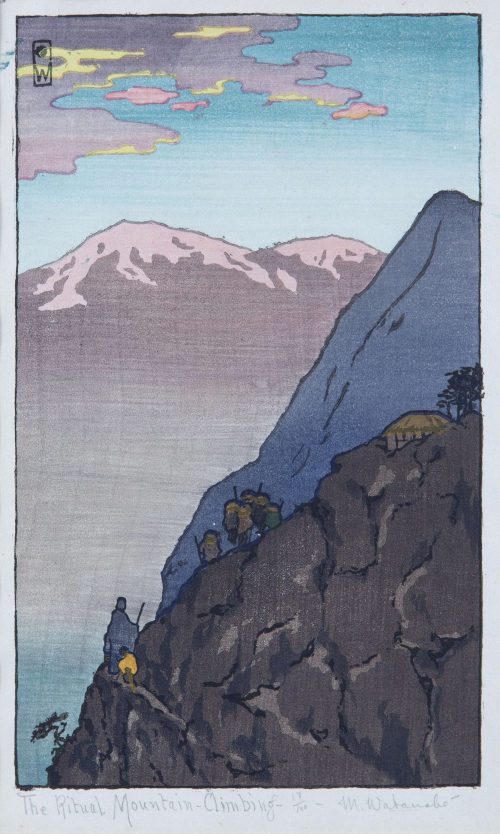

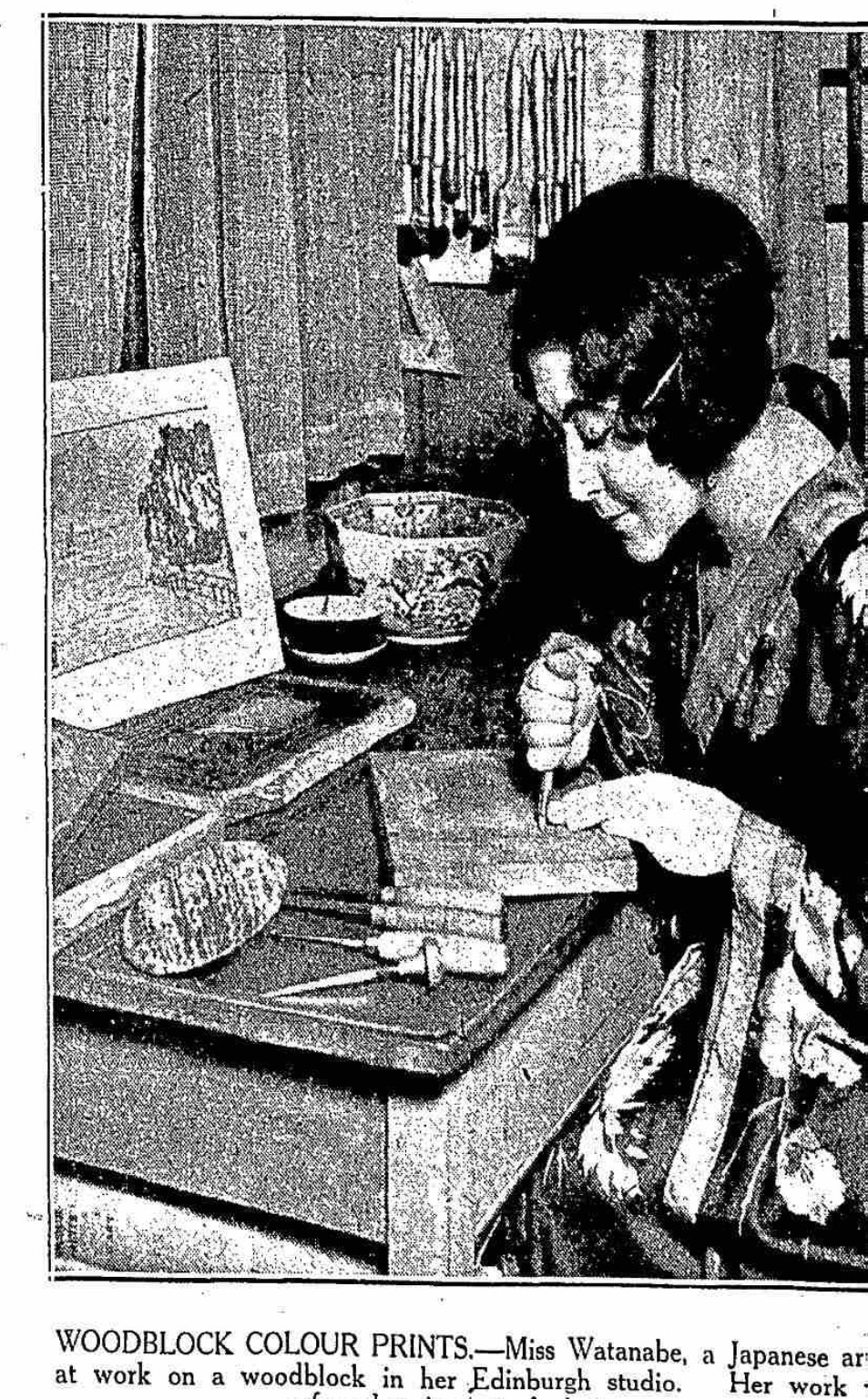

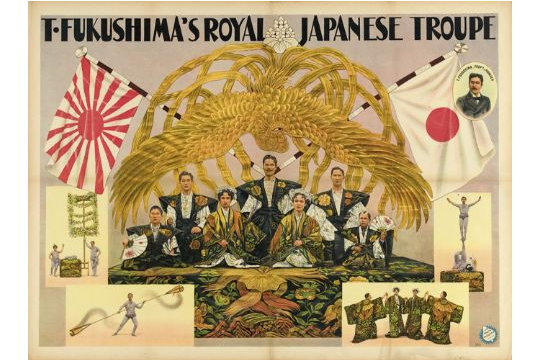

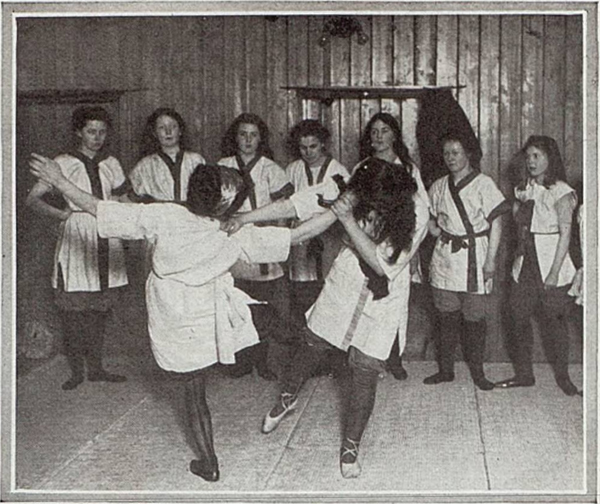

Along with the “wild men of Yesso,” the Japanese Circus comprised Japanese contortionists and athletes, a Japanese dwarf horseman 33 years of age, 36.5 inches high and Chung the giant clown. According to a review in May 1868, the wild men “did not arrive in time” to perform.

The Japanese circus continued to be advertised in the Irish press in the summer of 1868:

“Great Hippodrome and Japanese Circus – The Company was Organised in Japan, and have appeared in all the Principal Towns on the Continent of Europe : and in 1866 and 1867 they visited America, where they created the Greatest Sensation and Wonder, and every where received the most flattering Testimonials from the Nobility, Clergy, and Public, all the principal Cities of the United States and Canada.

The Manager of this Vast Establishment begs to assure the Inhabitants of Ireland that never, on any occasion, has there been a Circus this country with such on amount of Novelty, Talent and Real Amusement as is connected with this Japanese circus, and which will be brought before the Public at each performance—The Troupe includes— JAPANESE CONTORTIONISTS AND ATHLETES. Russian, British, American, and French Bare-Back Riders. Fascinating Troupe of Lady Equestrians, Gladiators, and Arab Vaulters, and a Magnificent Stud of Highly-trained Arab and Japanese HORSES, Mules, Ponies, Trained Monkeys, etc.

The Gorgeous Chivalric PROCESSION Entering the Town at ONE o’clock, extends the distance of half a-mile, headed the elegant Japanese Char-a-Banc or Band Chariot Mounted Warriors Glittering Suite of Armour; troupe of Fascinating Ladies, attired in Rich Costumes as Fair Dames of Ancient Chivalry; Kings and Queens on Thrones of State ; Comic Clowns in Comic Carriages, drawn Comic Ponies; and a number of Grand and Historical Tableaux.

Also the Massive Carriage, Containing the HORDE OF WILD MEN. The whole forming the most imposing sight ever witnessed. First Grand Tour through Ireland. The Entertainments will be varied at each Exhibition, and include Brilliant Equestrian Achievements, Daring Gymnastic Exploits, Grand Entrees and Cavalcades, Brilliant Spectacles and the Champion Troupe of Vaulters, Executing Feats of Air-diving and Turning Double Somershults. The Proprietors, the investment of an enormous capital, have brought together an amalgamation of Talent and Sensational Wonders that will combine all the real elements of Genuine Circus Performance, without the possibility of being equalled any similar Establishment, in this or any other Country.

In addition to other attractions will be found A HORDE OF WILD MEN from the Island of Yesso, the most Northern part of the Empire of Japan. These Aborgines of a wild mountainous country, landed at Southampton, January 23th, 1865, on the ship Constantine, Captain Menderfelt, and since that time have been exhibited in all the principal Towns in America, Russia, France, Germany, and England, where they have created the most extraordinary Sensation and Wonder. These wonderful people are now united with the Grand Japanese Circus, where they will appear at Mid-day and Evening Performance, in a Huge Wagon, and give vivid description of their Wild Hunting Exploits Flood and Mountain, Mode of Warfare, Native Dances, &c., &c.

To give additional spirit and excellency to this great Company’s Tour through Ireland, an engagement has been formed with the renowned MR. JAS. MACE, Who will appear each Performance, and give his unequalled representations of the Roman and Grecian Statues or Living Models of Marble Gems. N. B. those who have not seen Mr. Mace as the Statue, ’tis impossible to convey adequate idea of the effect produced. So surprising, so wonderful the illusion that the Spectator may fancy himself wandering through the Hulls of Rome and Florence, surrounded those splendid effects of human genius which have survived the destroying hand of time, and remain admiration of the civilized world. Hercules Struggling with the Namean Lion, Six Attitudes; the Slave Sharpening the Knife whilst overhearing the Conspirators, One Attitude; Achilles Throwing the Discus or Quoit, One Attitude ; the Fighting Gladiator. Three Attitudes; Ajax defying the lighting, One Attitude; the African Alarmed at Thunder On Attitude; Cain Killing Abel, One Attitude: Cain’s Remorse, One Attitude; Cain’s Flight, One Attitude; Roman fastening his Sandal, the dying Gladiator, Four Attitudes. Amongst the Artistes engaged will be found Celebrated Ladies and Gentlemen—Mons. Aguzzie, Mons. R. Silvester, Mons. J. Silvester, Signor Costelletto, Young Boorntze, Master Erviue, Pattir, Mr. John McDowell, Mr. Mace, Madame Aguzzie, Madame Mace, Madlle Cawline, Madlle Annette, Josephine, Miss Jenny Regan, Miss Lizzie Kite.

And the World-renowned —the CHARMED MONSTER BONELESS MAN, Who can dislocate and re-set any joint in his Body without pain or inconvenience. N.B.—Medical Gentlemen are particularly invited come and witness this Wonderful Performance.

The troupe of JAPANESE ACROBATS, their Miraculous feats Dexterity.

The various Acts and Scenes the Circle will be enlivened by those most necessary appendages of all first-class Equestrian Establishments, viz.:—good Laughter-provoking CLOWNS, headed by the Great American Jester, J. Costello !

The Japanese circus continued to tour Ireland to October 1868, but no further mention was made of the wild men of Yesso appearing.

The next and final appearance in Britain of the wild men of Yesso was in September 1870, with Howes & Cushing’s Great American Circus and Menagerie in Southampton and then in Shepton Mallet in October.