Another puzzle I wanted to solve during my recent trip to Nagasaki was whether Otaké really did visit Japan in 1886.

Tannaker Buhicrosan announced in The Era on the 11th December 1886 that his wife Otaké had departed for Japan on Friday 10th, for the first time in 20 years and that he had “engaged a special saloon and stewardess for her comfort. Her visit was meant to be of a private and family nature, but we believe she intends embracing the opportunity to secure several novelties and natives for her husband’s business, as it is the intention of Mr Buhicrosan to run to Villages in the provinces next year, as well as one in America, still keeping the one at Albert-gate open.”

There is no further mention of her visit in the English language press, nor does her name appear in any of the passenger lists for the P&O steamers that were the usual way to travel to Japan from Britain at that time.

If she had left for Japan in December, she would have been three months pregnant. She had returned to Britain by June 1887, when her daughter Chiyo was born, in Lewisham.

There was also no further mention of the declaration Tannaker had made when he first opened the Japanese Village in London, that the proceeds would be used to improve the position of women in Japanese society and promote Christianity there.

So if Otaké did go to Japan, were there any records of her visiting Nagasaki, and her home town nearby of Mogi and was there any evidence of her having recruited people for Tannaker’s new village?

Recruiting for the Japanese Village

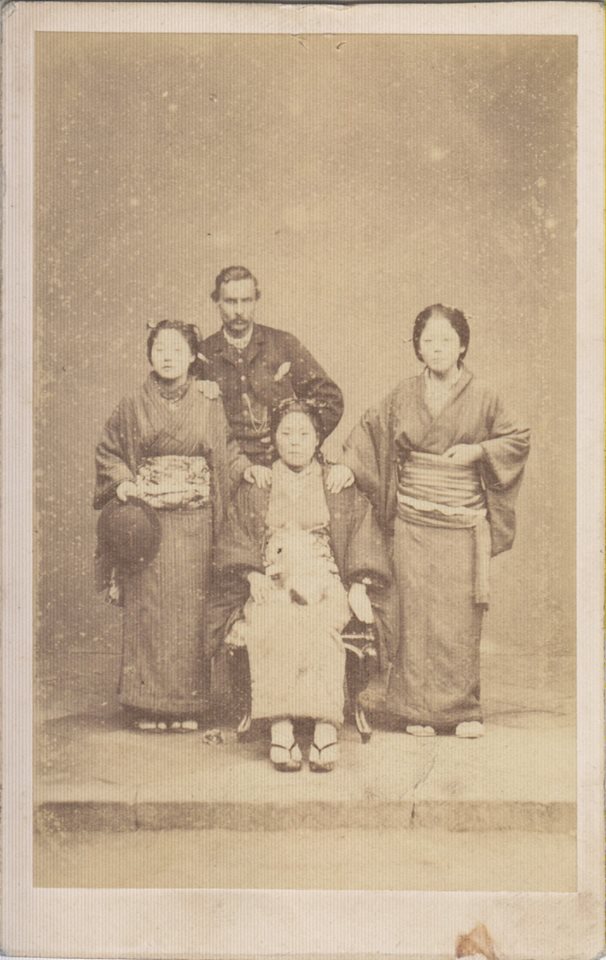

Tannaker visited Japan in August 1884, to recruit 50 (or 100) people for his Japanese Village in London, which opened in 1885. In an interview with the Yubin Hochi Shinbun he claimed that he only wanted high class craftsmen and performers, no geiko (Kyoto term for geisha) and that they would be looked after by his Japanese wife.

The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs raised concerns about Tannaker and his plan. Some of the recruits were then denied passports and it seems that in the end Tannaker took the Japanese group out of Japan with the undercover help of Charles Henry Dallas and his firm Rottman Strome, from Yokohama to Nagasaki and then presumably on to Shanghai.

The village opened in January 1885, but a fire in May forced its closure, and it reopened in Berlin. At least one Japanese person died in the fire, Enami Shonosuke (1863-1885) who had been employed as a wood carver. Tannaker returned to Japan to purchase further fittings in the summer of 1885.

The Berlin exhibition closed in August and then transferred to Munich, until the end of the year. The exhibition then reopened in London in December 1885. It came up against competion with a colonial exhibition with electric powered fountains opening in London in April 1886. Visitor numbers to Tannaker’s Village recovered in the autumn of 1886 but there were few sales of the more expensive items.

The Japan Weekly Mail noted in 22nd January 1887 that

“I fear by the frantic efforts which Mr Tannaker Buhicrosan is making to advertise his Japanese village at Knightsbridge that this interesting entertainment must be on its last legs.

He must have done uncommonly well with the Knightsbridge show, so perhaps he will retire on his fortune to Japan and there set on foot the various philanthropic and other schemes which he was so lavish in promising the British public a few years ago. The elevation of woman in the social scale was the principal one of these; it was, according to his account, a work that cried aloud for someone to do it, for the poor Japanese woman was in a terrible state.

He was, he observed, specially competent to pass an opinion on these subjects for his wife was a Japanese lady, who, under his tutelage, now saw the error of past ways, and the degradation of a position which she shared with all her countrywomen.

I should however do Tannaker the justice to say that once the show was fairly started, he said no more about social and religious forms.”

The Japan Weekly Mail‘s prediction proved to be correct. Tannaker sold the village to to the Japanese Village and Oriental Trading Company in January 1887, just after Otaké left for Japan.

The Japanese Village and Oriental Trading Company was owned by Marcus Samuel junior, founder of the Shell Transport and Trading Company which later became Royal Dutch Shell. The bankruptcy of the London Village in August 1887 may have been due to, or was one of the causes of, Samuel deciding it was better to focus on the oil business.

The Japanese villagers who had transferred to Samuel’s company took out court proceedings in October 1887, to sue for the funds for their passage home. Tannaker turned up to the hearing and offered support and to employ some of the personnel – but said that as he had already recruited new people for his new villages. One had opened in Saltaire in May 1887 and he opened a further one in Liverpool, in November 1887.

These new recruits had been spotted by the Rising Sun and Nagasaki Express, on 23rd February 1887: “a party of Japanese, male and female, left in the SS Cardiganshire for London yesterday, under agreement to join Mr “Tanaka’s” Japanese Village.”

The SS Cardiganshire was mostly used as a cargo ship rather than a passenger ship, so passenger lists were not published. Perhaps Otaké accompanied them to Britain, and had arrived in Japan by a similar arrangement. Journeys from Britain to Japan were taking at least 6 weeks at this point, so if she had left on December 10th, she would have reached Japan at the end of January or beginning of February. This would have given her 4 weeks to recruit and despatch the Japanese villagers.

Otake may have been assisted by Charles Henry Dallas but he had moved back to Shanghai in 1885. But perhaps he or his colleagues were able to help from there.

Otaké’s knowledge of Japan

As well as being nominated to look after the villagers while they were still in Tannaker’s employ, and then asked to recruit more personnel, Otaké was credited as the author of a guide to the Japanese Village, titled “Japan, past and present. The manners and customs of the Japanese, and a description of the Japanese native village”, published in 1885, reprinted in 1886. An online version of the 1885 edition can be seen here.

It was edited by Reinagle Barnett, which could lead to the supposition that he actually wrote it, and Otaké was just the front. But Barnett was no expert on Japan either. Examination of the text reveals that it is mostly a cut and paste job from the works of Rutherford Alcock, Isabella Bird and other visitors and residents to Japan.

It could be that the very act of compiling and commenting on these excerpts, and perhaps asking Tannaker what he had seen on his trips back to Japan, that forced Otaké to realise her knowledge of her home country was now very out of date. She may also have wanted to see her family again, to show them how far she had come since being sold into a teahouse. Without Charles Henry Dallas, and Tannaker’s rather poor record on looking after previous groups of Japanese, there was also a business case that she might be more trusted and able to recruit Japanese people.

Promoting Christianity

The only parts of the Japanese Village guidebook that read as authentically by Otaké are those dealing with Christianity and the role of women in Japan. She clearly had bitter recollections of the treatment of women in Japan, and as a recent convert to Christianity, may have felt a missionary zeal in returning to Japan.

Significant legal changes had already been implemented regarding women’s status in Japan, such as the emancipation of prostitutes in 1872 – although whether this had much impact is questionable. Christian evangelising was also far more permitted than before, with organisations such as the Salvation Army active in Japan by the 1880s, including rescuing “fallen” women.

Otaké had already been a Christian for several years before her putative trip to Japan. She had been baptized at St Mary’s Lewisham in 1883, taking on the Christian name of Ruth. Seven of her children with Tannaker were baptized at the same church the following year.

Tannaker claimed that he and Otaké were married in Nagasaki both by a Shinto priest and in a Christian ceremony in 1868. If true, the marriage must actually have been the year before, as they had sailed for Australia in 1867, when Otaké was 16 or 17. Strictly speaking, this marriage would not have been recognised in Japan or Britain. Marriages between foreign men and Japanese women were only officially permitted by the Japanese government in 1873. And if Tannaker was William Neville, then his first wife was still alive, and he would have been committing bigamy for the second time.

Neville/Tannaker’s first wife, Elizabeth, nee Carter, probably died in 1875 in Liverpool if she was the 34 year old Eliza Neville recorded in the Anfield cemetery register. A similar age Eliza Nevil had been living in Liverpool in 1871, with Elizabeth aged 9, the right age to have been Catherine Elizabeth Nevell, born to Elizabeth and William Neville/ Tannaker, in 1862.

It was not until four years after Elizabeth Neville’s death, however, in July 1879, that Otaké and Tannaker Buhicrosan were married in a registry office in Manchester. If Otaké was concerned about the treatment of women, one wonders what she made of Tannaker’s bigamy, which she must have known about, considering he acknowledged the daughters from his first marriage, the older of whom was living with the Tannakers in the 1880s.

Elizabeth Neville, the second daughter of Tannaker and Elizabeth, was recorded in the 1881 census as Laura Buhicrosan, at a boarding school in East Grinstead, and then as marrying John Hubbard in Australia later that year, as Laura Neville Buhicrosan.

She and John Hubbard had two children, and Elizabeth gave her maiden name as Catherine Elisabeth Laura Neville Buhicrosan on the register of their son’s birth.

Tannaker Buhicrosan was one of the directors of John Hubbard’s mining company which had been established in February 1887. Perhaps Tannaker bought his shares with the proceeds of the sale of the London Japanese Village.

Although the Tannaker’s home was in London, his marriage to Otaké took place in Manchester – where Tannaker’s Temple of Japan had been performing in July 1879. It was noted in The Era that several members of Tannaker’s Japanese troupe were to leave Britain to return to Japan – perhaps Tannaker was due to accompany them, and wanted to legitimize Otaké’s status before he left. Eight months later, Otaké and Tannaker’s 6th child and fourth daughter, Otakesan Maude, was born in London.

Tannaker’s name is in the registry office records as Tannaker Billingham Nevell Buhicrosan aged 38 and Otaké as Otakesan Ohilosan Buhicrosan, formerly Ohilosan, aged 32. Their supposed marriage in Nagasaki in 1868 was also noted. Tannaker gave his profession as merchant and his father’s profession as doctor, and name as William Nevell Buhicrosan deceased – not very Dutch sounding despite Tannaker’s earlier claims to be the son of a Batavian Dutch man. Otaké records her father as Haggrosan, a farmer – the same name she used as her maiden name in record of her baptism.

The treatment of women in Japan and Britain

Otaké and Tannaker stayed together until Tannaker’s death in 1894 at the age of 54, of cirrhosis of the liver and acute jaundice. Although this indicates Tannaker must have had a drink problem, there is no evidence that he mistreated Otaké as a consequence.

Otaké would have been aware, however, that the exploitation of women and domestic violence was not only a problem in Japan. The Matrimonial Causes Act came into force in Britain in 1878, providing protection for women who experienced domestic violence in their marriages. The act gave women the ability to obtain a protection order from a magistrates’ court, which was essentially a judicial separation that also granted them custody of their children.

One of the first men to be tried under it, in July 1878, was Thomas Edward Miles, who, with his wife Alice Edith, had been a witness to Otaké and Tannaker’s marriage in July 1879 in Manchester.

Thomas Edward Miles was the son of John Miles, a theatrical printer, who became a partner in Tannaker’s Japanese Village company in the 1880s.

It seems the Miles family connection to the Tannakers dated to at least 1878, as Miles Neville Buhicrosan, Otaké and Tannaker’s second son, was born in February 1878, and seems to have been given the name Miles in tribute to John Miles – perhaps John Miles was even Miles’s godfather. Or, it is speculated, his actual father, perhaps by Otaké, because when Miles later renamed himself, when living in South Africa, as Neville Miles, he claimed his father was John Miles.

A counterargument to this would be that laws heralding the apartheid era were beginning to be passed in South Africa, making it difficult for non-whites to own land. It may have been wise for Miles to claim as much white-sounding ancestry as possible, and distance himself from any exotic names.

The Croydon Times reported the Thomas Edward Miles case as follows on 10th July 1878:

“Thomas Miles, printer, No. 9, Great Titchfield-street, was summoned before Mr. Cook, for assaulting his wife, at present residing at Blyth-hill, Mr. Alsop appeared for complainant, and Mr. Parks for defendant —Mr. Alsop stated Mrs. Miles complained of constant ill-usage since her marriage, about three years ago. She had miscarried through the defendant’s violence. She had been repeatedly kicked and otherwise assaulted. On Wednesday last, on going to the defendant’s lodgings, in Charlotte street, the defendant said he would have his revenge on her, held a knife up, told her to get out of the room or he would throw he out, dragged her to the door, and her arm and knees were much hurt by her falling. The defendant was of intemperate habits, had been recently charged at that court with being drunk, and was so violent when under the influence of drink that he had torn his wife’s clothes off and held a razor over her while in bed—Mrs. Miles, a delicate, ladylike woman, deposed to various acts of ill-usage on the part of her husband, and to his irregular and intemperate habits, and then detailed the specific acts of violence to which she had been subjected on the day named in the summonses—Replying to Mr. Parks, complainant said her husband, when sober, was a good husband, and treated her kindly.—Mr. Parks having replied, and called a witness, Mr. Cooke said he had been asked to act under the new statute, but could only do so where it was shown that there was an aggravated assault. In the case before him he did not think that the evidence amounted to an aggravated assault, and what he should do was to call upon the defendant to find two sureties in the sum of £10 each to keep the peace towards his wife.”

A letter to the Daily News the next day from “Pitiful” read “will you further permit me to ask the presiding magistrate when he would consider the safety of this “delicate, ladylike woman,” poor Mrs Miles, to be “in peril,” since being “repeatedly kicked and beaten” – caused to miscarry, and threatened with a knife, and now with a razor, does not constitute “peril”? Surely when those drunken outbreaks of Thomas Miles some day reach their natural conclusion, and his wretched wife is killed by his kicks or his razor, a very dreadful responsibility will rest with the magistrate to whom the law confided the power to shield her, and who refused to use it.”

Tannaker and Otaké surely must have been aware of this case, and yet they asked Thomas and Alice to witness their own marriage a year later.

Thomas and Alice seem to have reconciled after the court case and decided to move to Lancashire, perhaps to try a fresh start. The advertisements for Miles’ printing business in London ceased after September 1879 and in June 1880 they had a son, John Miles, born in Salford. The 1881 census shows Alice, Thomas (who was working as a letter press printer), their nine month old baby John and a servant, living in Eccles New Road, in Salford.

The Tannakers returned to their home in Lewisham, however, although they may have continued to be in touch with Thomas and Alice through Tannaker’s business partnership with John Miles senior from 1883. Once Tannaker sold up his interest in the Japanese Village in Knightsbridge, in 1887, this partnership would have come to an end.

There is no sign of Thomas and Alice in the 1891 census, although an Alice Edith Miles (described both as married and as single) was admitted to Southwark workhouse in April 1888, and then admitted and discharged from the Southwark workhouse in July and August 1890.

An Alice E Miles died in Lambeth in 1934 – if it was Alice Edith Miles, then she lived until she was 80. As for Thomas Miles and their son John, there is no obvious record of either of them in the 1901 census nor records of death or marriage which match closely.

Tannaker was declared bankrupt in 1892, the same year that his old business partner John Miles died, at the age of 70. Miles was pre-deceased by his wife and both his daughters. Tannaker had his own family tragedy the year before, with the death of his four year old daughter Chiyo, after accidentally taking an overdose of Tannaker’s morphine.

As noted above, Tannaker died in 1894, of cirrhosis of the liver and jaundice. Otaké died twenty years later, on the eve of World War I.

Conclusion

Clearly someone must have recruited the Japanese people who travelled on the SS Cardiganshire in February 1887 for Tannaker’s new villages. Whether it was Otaké , on her first visit to Japan in twenty years, or someone else, is difficult to prove.

Otaké had plenty of reasons to want to visit Japan, not just to reconnect with her family and show off her wealth. She must have wanted to see for herself how far Japan had changed, both with regard to the influence of Christianity and the status of women. She may well have been able to persuade Tannaker that her trip would also make business sense, if she was able to recruit the new people he needed for his next Japanese villages.

But maybe, yet again, Tannaker was the master of self promotion, and having gained the publicity he wanted for his new villages, he simply used some of his old business contacts to find new recruits, thereby sparing the expense of actually sending Otaké in saloon class, with a stewardess.